3 steps away from success!

- Complete the order form with details of your assignment.

- Experienced professional writer will research and write your paper

- You will receive an original work that meets you needs

| Introduction | 1 |

| Why this guidance has been developed | 1 |

| Why follow this guidance? | 1 |

| Scope of this Guidance | 2 |

| Individualised Risk Assessment | 2 |

| Supporting Tools | 3 |

| Statement of Intent | 3 |

| General Principles of Oral Health Assessment and Review | 4 |

| What is Oral Health Assessment and Review? | 4 |

| Overarching Principles of Oral Health Assessment and Review | 6 |

| Communication | 6 |

| Medico-legal Issues Relevant to Oral Health Assessment and Review | 7 |

| Record Keeping | 10 |

| Assessment of Patient Histories | 12 |

| Assessment of Oral Health Status | 15 |

| Assessment of the Head and Neck | 15 |

| Assessment of the Oral Mucosal Tissue | 16 |

| Assessment of the Intra-oral Bony Areas | 17 |

| Assessment of the Periodontal Tissue | 18 |

| Conducting a Periodontal Examination | 19 |

| Assessment of Teeth | 21 |

| Assessment of Dental Caries and Condition of Restoration | 21 |

| Assessment of Tooth Surface Loss | 24 |

| Assessment of Tooth Abnormalities | 25 |

| Assessment of Fluorosis | 26 |

| Assessment of Dental Trauma | 27 |

| Occlusal Assessment | 29 |

| Orthodontic Assessment | 30 |

| Assessment of Dentures | 33 |

| Diagnosis and Risk Assessment | 35 |

| Risk Assessment Process | 36 |

| Identifying Modifying Factors, and Diagnosing Disease | 36 |

| Evaluating the Impact of Modifying Factors | 36 |

| Predicting Future Disease | 37 |

| Identifying the Overall Risk Level | 38 |

| Identifying a Risk-based Review Interval | 38 |

| Personal Care Plan and Ongoing Review | 40 |

| Developing a Personal Care Plan | 41 |

| Ongoing Review | 43 |

| Clinical Governance, CPD and Training | 45 |

| Recommendations for Audit | 45 |

| Recommendations for Research | 45 |

Introduction

Why this guidance has been developed

Following the earlier surgical (or extractive) era, there has been a restorative approach to the provision of dental care in primary practice, with a focus on the assessment of carious cavities in teeth and less emphasis on initial caries, the assessment of periodontal tissue and the overall oral health of the patient. A standard recall interval of 6 months has been advocated for all patients, regardless of the status of the patient’s oral health. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that there are wide variations between patients in their susceptibility to disease, the likelihood of early disease progressing and the speed of disease progression, if it occurs. A ‘one-size’ fits all approach is therefore not adequate to meet the needs of every patient.

In 2004, the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)1 issued guidance recommending that a patient’s recall interval for routine care be determined by their overall risk of oral disease and thus be individualised to the needs of each patient. In addition, the Scottish Government has more recently set out a ‘Better Health, Better Care’ Action Plan2 that targets health inequalities and those at greatest risk and aims to improve health and the quality of healthcare by adopting a more preventive, proactive approach. This model is referred to as anticipatory care and aspects of it are already being implemented in dentistry within the Childsmile programme3. The intention is to extend this approach across the whole of primary dental care to move from the more traditional approach towards a more preventive, evidence-based and, where possible, minimally invasive approach to care. This approach is risk-based and long-term and aims to meet the specific needs of individual patients and encourage the involvement of patients in managing their own oral health.

The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) convened a guidance development group to provide clinical guidance on best practice for the assessment of individual dental patients. The Guidance Development Group defined an oral health assessment (OHA) as assessment of the patient’s histories and their oral health status, leading to diagnosis and risk assessment, followed by personalised care planning and review. Many aspects of the guidance will be familiar to dental teams. However, the ‘newer’ concepts introduced include: assessing modifying factors (including risk and protective factors, behaviours and clinical findings associated with the development of oral disease or conditions) and assigning a ‘risk level’ to each patient in order to facilitate the development of a personal care plan and the identification of a recall interval for review that is specific for each patient (see Sections 5 and 6). This guidance therefore promotes a systematic and comprehensive approach to assessing and managing the overall oral health of each patient. Further details about SDCEP and the development of this guidance are given in Appendix 1.

Why follow this guidance?

If a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s overall oral health status, including assessment of teeth, periodontal tissue, oral mucosal tissues and head and neck, is carried out for all patients, signs of oral disease can be recognised early and appropriate care (both preventive and treatment-based) can be provided to improve the oral health, and in some cases general health, of the patient population in Scotland.

If accurate and comprehensive record keeping is carried out, this will facilitate the provision of high-quality patient care and improve patient safety, particularly in cases where patient care is shared among the dental team4. It also provides a permanent record, which can support the dental team if faced with complaints or litigation.

Scope of this Guidance

This guidance aims to facilitate individualised long-term preventive-orientated care (including recall) to improve and maintain the oral health and general health of each patient by providing advice on patient assessment (see Section 2.1). The guidance is based on existing guidance (NICE Clinical Guideline 19 on dental recall1, FGDP Clinical Examination and Record Keeping guideline5), relevant systematic reviews6-8, research evidence and the opinion of experts and experienced practitioners.

This guidance is directed at the whole primary care dental team. The approach to patient assessment described in this guidance is applicable to all patients, including adults, children and those with special needs, who would normally receive regular care in the primary care sector but needs to be adapted to the particular needs of specific patient groups. With the exception of some differences for the assessment of child patients which are highlighted, details of such adaptations are beyond the scope of this version of the guidance.

For patients who attend only for urgent care (e.g. pain relief), this approach is not appropriate

Instead, a basic assessment that enables the management of the patient’s immediate needs is sufficient. This should also always include taking a medical history and examination of oral mucosal tissue. Such irregular symptomatic attenders should be invited to attend for regular care, which would begin with a comprehensive OHA.

The guidance does not include detailed treatment planning or specific clinical procedures. Please refer to the SDCEP guidance ‘The Prevention and Management of Dental Caries in Children’9 for more detailed advice related to child patients.

This guidance describes:

Individualised Risk Assessment

Formal individualised risk assessment is one of the newer concepts introduced in this guidance. The guidance is therefore structured to facilitate this process. Assessment of the patient’s risk of developing oral disease is an imperfect science, and requires clinical judgement and experience (often of the whole dental team) to assess and re-assess the level of risk for each individual patient (see Section 5). A range of factors need to be considered when assessing the level of risk. Within Sections 3 and 4, modifying factors, are listed in alphabetical order to facilitate risk assessment for each patient. Modifying factors include:

Modifying factors need to be considered by the dental team when assessing the level of risk for the key elements of oral health for each patient and the period before the next review. For many of these factors, there is evidence to support their association with the development of oral disease1,10,11. Inclusion of other factors and clinical findings are based on the consensus of the Guidance Development Group; these are indicated by the symbol §.

The risk factors and clinical findings, together with the clinician’s knowledge of the patient’s attitude to care and willingness and ability to cooperate, are used to determine the patient’s overall level of risk (low, medium or high), to develop each patient’s personal care plan and to identify a recall interval that is specific to the individual patient (see Sections 5 and 6 for more details of this process). A form to facilitate the recording of risk levels and to help communicate this with patients is provided in Appendix 9 (Patient Review and Personal Care Plan).

Supporting Tools

Example forms are provided in Appendix 9 to facilitate the recording of information from the various elements of the assessment. The Guidance Development Group considers it best practice to record all information contained in these forms when conducting a comprehensive Oral Health Assessment; however, the precise form or system used to collect this information is the choice of the individual practitioner. Forms for the assessment of occlusion and for assessment of other elements of the OHA that generally affect only a small proportion of patients (e.g. intra-oral bony areas, trauma) are not provided; however, it is important to record positive findings of these assessments in the patient’s notes. Appendix 9 also includes a checklist to assist with recording which elements of assessment have been conducted at a particular visit and the outcomes of the assessment.

Other appendices provide additional information on, for example, the roles and responsibilities of members of the dental team, radiography and charting caries.

Guidance in Brief’, a summary version of this guidance, and a Quick Reference Guide that illustrates some of the key concepts are provided separately.

Statement of Intent

This guidance has resulted from a careful consideration of current legislation, professional regulations, the available evidence and the opinion of experts and experienced practitioners. It should be considered when conducting any examination and discussing care planning with the patient and/or carer. As guidance, the information presented here does not override the health professional’s right and duty to make decisions appropriate to the individual patient. However, it is advised that significant departures from this guidance are fully documented in the patient’s clinical record at the time the relevant decision is made. This approach to assessment incorporates improved monitoring to underpin the provision of high-quality patient care and reflects changes taking place internationally. It is appreciated that fully implementing this approach may represent a significant change to current practice for some dental teams and will take time. However, dental teams could implement the guidance incrementally and it is recommended that these changes are planned and documented

General Principles of Oral Health Assessment and Review

What is Oral Health Assessment and Review?

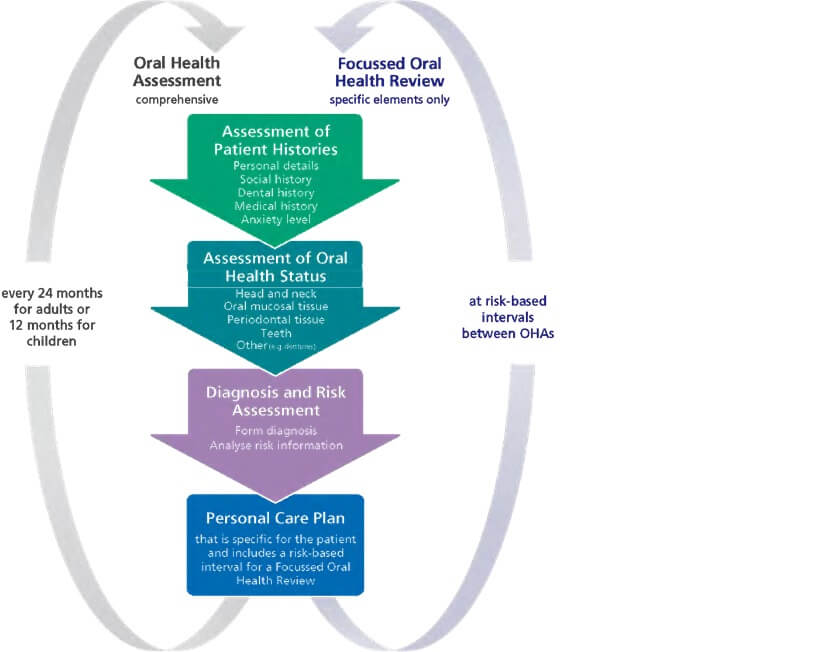

Within routine primary dental care, Oral Health Assessment and Review (OHAR) involves a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s social, dental and medical histories and oral health status that leads to diagnosis and risk assessment, followed by personalised care planning and ongoing review (see Figure 1).

A key aim of Oral Health Assessment and Review is to facilitate the move from the traditionally restorative approach to patient care to a more preventive and long-term approach that is risk-based and meets the specific needs of individual patients. It also aims to encourage the involvement of patients in managing their own oral health.

The personal care plan is a risk-based, long-term plan that is specific for the individual patient. Its aim is to address the patient’s individual oral health improvement needs by including preventive options (e.g. patient advice, topical fluoride), operative interventions if required (e.g. restoration), the interval for review, referral for specialist advice and/or treatment if required and long-term maintenance (see Section 6 for more details).

For a personal care plan to meet the changing needs of a patient, it is important that on registering with a dental practice, each patient receives a baseline comprehensive Oral Health Assessment (OHA). For adults, this is repeated after 24 months up to the age of 18 years1. For children, the first comprehensive assessment should be conducted as early as possible, and no later than three years of age, and be repeated at 12 month intervals. In addition, during these time periods Focussed Oral Health Reviews (FOHRs) can be carried out. Both the number of FOHRs and the intervals between them will vary depending on the patient’s risk of future oral disease.

For patients who attend only for urgent care (e.g. pain relief), this approach is not appropriate. Instead, a basic assessment that enables the management of the patient’s immediate needs is sufficient. This should also always include taking a medical history and examination of oral mucosal tissue. Such irregular symptomatic attenders should be invited to attend for regular care, which would begin with a comprehensive OHA.

This guidance describes the elements of Oral Health Assessment and Review. The process is illustrated in Figure 1, and described in detail in Sections 3–6. Actions for the dental team are shown as bulleted lists in coloured boxes and diagrams are included to illustrate general concepts. Additional resources to assist the dental team in following this guidance are highlighted throughout and included in the appendices.

Figure 1 Overview of Oral Health Assessment and Review

Overarching Principles of Oral Health Assessment and Review

The increased awareness that oral health is an important component of general health, combined with a desire to improve the general well-being of patients and patient safety, is an important driver for thoroughly assessing a patient’s oral health. There are three overarching principles that facilitate the delivery of quality care and that are beneficial to both the patient and the dental team: effective communication (see Section 2.2.1); practising within medico- legal constraints (see Section 2.2.2); and comprehensive and accurate record keeping (see Section 2.2.3).

It is important that details of a comprehensive assessment of the patient histories (see Section 3) and their oral health status (see Section 4) are recorded clearly and accurately, retained within the patient record (see Section 2.2.3) and that the findings and modifying factors (see Section 5) are discussed with the patient to assist in the development of a mutually acceptable care plan (see Section 6). This should:

Communication

Communicating effectively to help build a strong ‘dental team–patient’ relationship is an essential component of providing appropriately tailored, quality dental care12-14. For example, although identifying and managing the oral health risk of each patient is the responsibility of the dental team, the patient has a key role in providing accurate information (e.g. medical conditions, diet, smoking habits) (see Section 3) to help the practitioner make informed decisions.

The patient can also play an important role in reducing or mitigating some risk factors (e.g. improving oral hygiene, reducing alcohol consumption, reducing the frequency of sugar intake). Therefore, it is important to emphasize to the patient the need to answer the questions regarding social history, dental history and medical history honestly, and to discuss the concept of risk and the patient’s role in managing this risk. Forms for recording information relating to elements of OHAR are provided in Appendix 9. These forms provide a starting point for discussion with the patient and, depending on the answers to the questions, further questions and communication might be required, and relevant results recorded in the patient’s notes. A form to facilitate the recording of risk levels (see Section 5) and communicating this with patients is included in Appendix 9 (Patient Review and Personal Care Plan).

Effective communication with patients will also minimise misunderstandings and the possibility of future complaints or litigation (see Section 2.2.2)15.

Clear communication among the dental team is also essential to minimise misunderstandings and ensure the best possible care for patients4. It is important that each member of the dental team knows and keeps up to date with the responsibilities of each dental team member as these can change over time. Current roles of the members of the dental team are outlined in Appendix 3.

The communication skills of listening, questioning and explaining (as well as an understanding of verbal, non-verbal and written communication) are central to any ‘dental team–patient’ interaction. It is important to gauge the level of understanding of the patient and adjust your communication style and method to suit the patient.

Communication with child patients brings with it additional complexity and requires additional lines of communication with the child’s parent or carer. When providing care for younger children, the dentist’s relationship with respect to gathering information will primarily be with the parent or carer. However, this will change with the age and understanding of the child and it is important, even for the young child, to include them in any conversation and not ‘talk over’ them; this will ensure that the child is happy with the meaning of any information being shared with the parent/carer and help to build on the concept that child patients have a role in what is being decided about their care. The key to communicating with child patients is to remember that communication is not just about words: use age-specific language and ensure, where possible, that the environment is appropriate (e.g. use a children’s area or children’s books and toys)16. The SDCEP guidance ‘The Prevention and Management of Dental Caries in Children’9 provides further advice on providing care to children and involving child patients in the management of their care

Medico-legal Issues Relevant to Oral Health Assessment and Review

OHAR involves several processes, each of which must be conducted within medico-legal constraints. The principle legal concepts relevant to OHAR are:

It is important that practice staff are familiar with those aspects of medical law that impact directly on their area of practice and that this is reflected in staff training.

Confidentiality and Disclosure of Information

Dentists have a duty of confidentiality to their patients, and disclosure of personal health information without consent is governed by the ethical guidance of the General Dental Council (GDC)4,18,19 and the Data Protection Act 199820,21. Personal health information includes all notes, radiographs, photographs, details of treatment carried out, records of appointments, payments made and any personal information about the patient.

Information obtained in the course of OHAR must be treated in the strictest confidence. Members of staff might be asked to assist patients in completion of the ‘History’ sections of forms used as part of OHAR. All such staff must be aware of confidentiality issues and be suitably trained for the tasks they undertake22. The design and layout of surgery premises should also reflect the requirements of confidentiality.

Consent and Capacity

It is a general legal and ethical principle that you must obtain valid consent before starting treatment or physical investigation, or providing personal care for a patient24. OHAR involves examination of the head, neck and oral tissues. In addition, diagnostic tests such as radiographs might be undertaken. It is important that patients are aware of what is planned in the course of OHAR and that they consent to what is proposed. It is also important to note that a patient might be unable to consent on their own behalf, and patients with capacity and over 16 years of age have the right to refuse care and withdraw consent at any time and that this must be respected.

There are four general principles to obtaining consent before beginning clinical treatment or investigation: the capacity to consent, providing adequate information, the freedom to choose and that consent is an ongoing process.

The following groups of patients can consent to medical or dental treatment, investigation or personal care:

Note that the law governing consent varies across the United Kingdom, and therefore practitioners must familiarise themselves with the law relating to the country in which they intend to practise.

General points to note

Recording of consent process

Refusal or incapacity to consent

Record Keeping

Good record keeping underpins the provision of quality patient care5. Increasingly, the care of patients is shared among dental team members and between other professionals. Therefore, it is important to practise good record keeping to ensure that all relevant information is available to facilitate the provision of effective, long-term shared care of patients. If carried out consistently for each patient, it will also save time in the long run for the dental team and will provide a permanent record of the care of patients, which is essential for medico-legal reasons (see Section 2.2.2).

An increasing number of dental practices use software with automated data collecting and charting. It is anticipated that the increasing use and development of IT across all of dental primary care will greatly facilitate data collection, use and re-use of risk information, histories and examinations.

In the meantime, example forms to facilitate recording of information are provided in Appendix 9. It is important to note that the information gathered represents a starting point for discussion with the patient and, depending on the answers to the questions, further questions, investigations or actions might be required and the relevant results of these investigations recorded in the patient’s notes.

General Principles

Recording Information for Individual Patients

For child patients

Assessment of Patient Histories

Formally, the first stage of OHAR is the assessment of patient histories. However, the assessment of the patient actually begins as soon as the s/he enters the practice or surgery. The patient’s gait, posture and mood can provide information on the general well-being of the patient, which can have an impact on their oral health. Engaging the patient in conversation as they enter the surgery also enables the dental team to develop their initial assessment while establishing whether the patient is able to fully understand the information they are given verbally. This can help to identify those patients who might require extra support in understanding the dental care they are to receive, including their role in the management of their oral health and any future treatment plans.

Children and patients with special needs will require varying levels of support in order to attend for care. It is important to engage children in conversation to encourage their involvement in their dental care. The BDA case mix tool34,35 provides a means of weighting key areas such as the ability to communicate and the ability to cooperate, in addition to weighting access to care, medical status, oral health risk and relevant legal and ethical issues

Most patients will be able to provide this information by completing a form. Some might require assistance with some or all of the questions. For children or patients requiring additional support, it might be necessary to collect some of the above information from parents or carers. Modifying factors identified in this initial assessment of patient histories can help inform other elements of OHAR [e.g. low socioeconomic status is associated with high caries levels36, smoking is associated with poor periodontal status40, adverse effects of medications on oral soft tissues and systemic disease (e.g. diabetes or cardiovascular conditions) might impact on treatment provision]. The most common risk factors are highlighted at the end of this section to aid identification of the level of risk for this element of OHAR . These risks, together with risks identified in other elements of OHAR, inform the development of a personal care plan .

Box 1 Assessment of Patient Histories – Modifying Factors

Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Oral Disease Medical

Social and dental

Protective Factors Associated with the Development of Oral Disease

Assessment of Oral Health Status

Assessment of the Head and Neck

Assessment of the head and neck involves an initial visual assessment of the head and neck and then palpation of the lymph nodes and temporomandibular joints (TMJ) for all patients. It is conducted after the patient histories (see Section 3) have been taken and any significant findings noted but before the intra-oral examination and any treatments are carried out (see Figure 1). This enables knowledge of the patient’s histories to inform the assessment of the head and neck and increases the likelihood that potentially serious conditions (e.g. facial fractures or basal cell carcinomas/rodent ulcers of the face) are diagnosed and that care planning is specific for the individual patient. The most common clinical findings are highlighted at the end of the section to help inform the development of the personal care plan (see Section 6).

Box 2: Assessment of the Head and Neck – Modifying Factors

Clinical Findings

Assessment of the Oral Mucosal Tissue

Thorough examination of the oral soft tissues is an important part of any dental examination and should be carried out whether the patient is dentate or edentulous. Changes in the oral mucosa might highlight underlying conditions (e.g. infections and diseases of the blood, gastrointestinal tract and skin) and so a thorough examination carried out by dentists might lead to an earlier diagnosis of such conditions. The patient’s medical history might identify medications or systemic diseases that could impact on oral soft tissues and the patient’s social history might highlight certain lifestyle factors that could be injurious to oral health, such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption and poor diet; therefore, it is important that patient histories (see Section 3) are taken prior to assessing the oral mucosal tissue.

There are also some conditions that affect the lining of the mouth, such as white, red or speckled patches, which might be painless and thus easily missed without careful examination. This is particularly true in relation to oral cancer, which is often painless in the early but treatable stages.

During the period 1990–1999, the incidence of oral cancer in Scotland increased by 34% in both males and females59 and in 2007 there were 673 new cases or oral cancer diagnosed in Scotland, an incidence that is substantially higher than that of England and Wales60. Important ‘lifestyle’ behaviour factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption (which together have a synergistic effect) and a diet low in fresh fruit and vegetables relate to the incidence of oral cancer. The aetiology of oral cancer is complex but most patients with oral cancer smoke and/or drink alcohol to excess. An 11-fold increased risk of oral cancer with cigarette smoking has been shown60,62, and Rothman63 states that almost 80% of all cases of oral cancer can be attributed to tobacco. There is also a clear association between oral cancer and social deprivation (low SIMD; see Appendix 2 Glossary).

Because of the link between smoking and oral lesions it is important that the patient’s smoking status is established and checked at every review appointment, and the patient is given advice on the value of stopping smoking. It is also important that the patient’s alcohol consumption is recorded and advice is given on the safe levels of consumption

Box 3 Assessment of the Oral Mucosal Tissue – Modifying Factors

Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Oral Disease

Clinical Findings

Mucosal lesion present with particular concerns for:

Assessment of the Intra-oral Bony Areas

It is important that the intra-oral bony areas (tooth-bearing alveolar bone, the hard palate) are examined visually and palpated to assess any abnormalities that might affect the patient’s treatment (e.g. if there is extensive destruction of the alveolar bone by periodontitis, advanced restorative care might not be advisable; if there are poor ridges, it might be difficult to create dentures that have good retention).

| Cawood and Howell classification of denture-bearing bone | |

|---|---|

| Class I | Dentate |

| Class II | Immediately post extraction |

| Class III | Well-rounded ridge form, adequate in height and width |

| Class IV | Knife-edge ridge form, adequate in height and inadequate in width |

| Class V | Flat ridge form, inadequate in height and width |

| Class VI | Depressed ridge form |

Box 4 Assessment of the Intra-oral Bony Areas – Modifying Factors

Clinical Findings

Assessment of the Periodontal Tissue

Careful recording of a patient’s medical and social history is important to assess the patient’s risk of periodontal disease because poor oral hygiene habits72, smoking40 and diabetes73 are all known to be risk factors for periodontal disease. Recent studies have also highlighted associations between periodontal disease and several systemic conditions74-78, although no causal links have been demonstrated. The British Society of Periodontology recommends the use of the basic periodontal examination (BPE), with appropriate radiographs, as a simple means of screening of the periodontal tissue within primary dental care79 to indicate the level of examination needed and to inform the care plan for each patient.

The BPE is performed on all dentate patients aged 12 and over. For patients aged 12-17 recording should only be taken on the following index teeth within each sextant80:

NB: The International Dental Federation (FDI) tooth notation system has been used above (see Appendix 4).

The BPE requires the periodontal tissue to be examined with a standardised periodontal probe using light pressure (20–25 g) to examine the tissue for bleeding, plaque-retentive factors and pocket depth (see Table 1)Table 1 Basic periodontal examination codes

| BPE Code | Visible signs |

|---|---|

| 0 | No pockets >3.5 mm, no calculus/overhangs, no bleeding after probing |

| 1 | No pockets >3.5 mm, no calculus/overhangs, but bleeding after probing |

| 2 | No pockets >3.5 mm, but supra- or subgingival calculus/overhangs |

| 3 | Probing depth 3.5-5.5 mm (black band partially visible, indicating pocket of 4-5 mm) |

| 4 | Probing depth >5.5 mm (black band entirely within the pocket, indicating pocket of 6 mm or more) |

| * | Furcation involvement |

Table 2 Levels of treatment complexity detailed by the British Society of Periodontology

| Complexity 1 | BPE Code 1–3 in any sextant |

| Complexity 2 |

BPE Code 4 in any sextant Surgery involving the periodontal tissues |

| Complexity 3 |

BPE Code 4 in any sextant and one or more of the following factors:

Diagnosis of aggressive periodontitis as assessed either by severity of disease for age or based on rapid rate of periodontal breakdown; Patients requiring surgical procedures involving tissue augmentation or regeneration, including surgical management of mucogingival problems; Patients requiring surgery involving bone removal (e.g. crown lengthening); Patients requiring surgery associated with osseointegrated implants |

Conducting a Periodontal Examination

Box 5: Assessment of the Periodontal Tissue – Modifying Factors

Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Oral Disease

Clinical Findings

Assessment of Teeth

The need to accurately assess the dentition and record a baseline or initial charting is fundamental to risk management in general dental practice85. Accurate assessment of the dentition and maintenance of good quality up-to-date records are important for:

A comprehensive assessment of teeth includes assessment and recording of:

Assessment of Dental Caries and Condition of Restorations

Dental caries remains a significant problem in Scotland and recording the presence of carious lesions and restorations is a key element of assessing the condition of the teeth and oral health.

Dental caries is a process of tissue damage that occurs on a continuous scale from subclinical surface changes to the presence of large pulp-exposing cavities. Early lesions can progress forwards on this scale (towards increasing damage) or backwards (towards tissue repair), depending on the balance of the demineralisation–remineralisation process.

Recording the location and extent of each lesion is important for the planning and monitoring of an individual care plan that comprises preventive and maintenance elements together with operative (intervention) elements, where required. The presence of restorations and the material used for each restoration should also be recorded.

The shift in philosophy of care from a traditional surgical-only model to a preventive, minimally invasive approach using fluorides and fissure sealants has been advocated by the FDI86 and many other agencies for many years. This shift, together with the wide-scale implementation of community-based and practice-based caries prevention programmes across Scotland (e.g. Childsmile)3, increases the need for a more detailed approach to recording and monitoring the caries process.

Currently, dentists use a variety of charting systems, although a baseline standardised charting system with International Dental Federation (FDI) tooth numbering is recommended to highlight the patient’s clinical caries status before treatment. In 2004 a review87 identified 29 different criteria based systems for identifying caries, 13 from the UK alone. Seven of these systems measured non-cavitated as well as cavitated active caries lesions. The review concluded that there was a need to define one system that has content validity based upon current scientific evidence and the consensus of experts in the fields of cariology and restorative sciences. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) (www.icdas.org) has been developed by expert consensus based on international best evidence88-90 in response to these findings. It has been designed for use in dental clinical practice, as well as in education, clinical research and epidemiology.

ICDAS is a clinical visual scoring system91,92 that provides a simple way of grading or ‘staging’ the severity of carious lesions on a scale of 1–6, based on the clinical visual appearance of the lesions (see Appendix 7). This scale has been shown to correlate well with the histological extent of dental caries within the tooth, and enables the collation of high-quality information on caries status to help inform decisions about appropriate diagnosis, prognosis and clinical management at the individual patient level. Caries activity status can also be recorded with the system, frequently with a + denoting active lesions and a – denoting inactive lesions.

ICDAS facilitates the type of long-term, prevention-orientated, caries control that is now advocated by many dental organisations and authorities, including the FDI86,93, and that is often referred to as ‘minimally invasive (MI) dentistry’. The use of ICDAS in this context is supported by the British Dental Association’s Health and Science Committee and the European Global Oral Health Indicators Development Programme (EGOHID)

While ICDAS has undergone extensive testing in the research and epidemiology arenas, its testing in the general practice environment has been more recent95,96 Further developments are in train to enhance the practicalities of its application in general practice as the International Caries Classification and Management System - ICCMS™ 97,98 ICDAS is considered by many as the most promising system for the thorough recording of caries and restorations. Integration of ICDAS codes with practice management systems is also currently in development.

Further details of ICDAS can be found in Appendix 7. A free e-Learning Programme explaining the ICDAS method is available at: www.icdas.org/elearning-programmes.

Diagnostic Aids for Dental Caries

Radiography

Bitewing radiography (see Appendix 5) has traditionally been used in combination with visual inspection for comprehensive caries diagnosis at the individual patient level. Indeed, several reviews show that radiographs are more sensitive than visual inspection for detecting both approximal and occlusal lesions99-101. These diagnostic benefits have to be balanced against the known, low but real, risks associated with ionising radiation. The dose of radiation must be kept as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) for each patient84.

Current digital radiograph systems have been reported to be as accurate as traditional films for caries detection6 and offer other benefits in that they can be more easily shared with colleagues. They also offer the prospect of enhancements such as subtraction radiography, although these techniques are not yet available for general practitioners.

| Patient Group | Frequency of Radiographs |

|---|---|

| High-risk children and adults | Every 6 months until no new or active lesions are apparent |

| Moderate-risk children and adults | Every 12 months until no new or active lesions are apparent |

| Low-risk children with primary and mixed dentition | Every 12–18 months |

| Low-risk adults and children with permanent dentition | Every 2 years; consider extending the interval if continuing evidence of low caries activity |

Other diagnostic aids exist for the detection of caries. Details of each are given below. However, it is the clinician’s responsibility to decide on the best option for each patient. Note that although there might be advantages in increased sensitivity, the DIAGNOdent, electronic caries monitor and cariometer methods can also give rise to false positive readings.

Tooth separation

The use of temporary tooth separation for a period of 3–7 days enables better visual access to the approximal surfaces of teeth and can improve caries diagnosis

Optical caries detection

The two best known optical caries detection systems are FOTI (fibre optic transillumination104 and DIAGNOdent105. Both systems have been used widely in clinical trials and have been shown to have the potential to increase diagnostic yield. However, they have not been used widely in general practice and are prone to inter-operator variability.

Electronic caries monitors

Detection of caries using the electrical resistance measurements [electronic caries monitor (ECM)106 and cariometer (CRM)] has also been tested with some success. As with the current optical systems, the initial systems have suffered from inter-operator variability; they have not been widely available until recently.

Salivary tests

In some countries salivary tests have been used for many years to identify high-risk individuals on the basis of microbiological assessment. These methods tend to reflect data on only a limited proportion of the potentially cariogenic and complex biofilm, and, at the individual patient level, offer disappointing diagnostic performance. Although they might be an aid to patient motivation and education, at present they do not appear to offer significant benefit over and above detailed clinical oral health assessment.

Assessment of Tooth Surface Loss

Tooth surface loss (tooth wear) is tooth substance loss that is not caused by trauma or caries. The loss of tissue is a surface phenomenon of clean tooth surfaces, unlike caries where much of the loss is initially from the subsurface enamel covered by biofilm (plaque). Tooth surface loss can be divided into three categories (see Appendix 2 Glossary for definitions):

It is important that any type of tooth wear is recorded as part of a patient’s baseline examination. In cases where tooth wear is detected, it is important to establish the main type of dental wear present (the three wear types can exist simultaneously), and also the underlying reason for the condition, which will aid the tailoring of preventive plans and advise possible referral to, for example, a general medical practitioner. It is important that the dental team monitors tooth wear cases to establish possible lesion progression. Baseline study casts can assist in monitoring progressions but there are no validated monitoring systems available at present. The related theoretical process of abfraction is defined in the Glossary.

Diagnostic Aids for Tooth Surface Loss

The key diagnostic aids for the monitoring of tooth surface loss are study models or clinical photographs. Either of these will enable a backward comparison to assess both the rate and the extent of any surface loss. Clinical assessments are important and several indices are under development for use in general dental practice; although these have yet to be validated in this setting, they might prove useful in the future.

Assessment of Tooth Abnormalities

Tooth abnormalities can be divided into the following categories.

Diagnostic Aids for Tooth Abnormalities

Radiography

Intra-oral radiographs of the affected tooth or teeth are used to assess tooth abnormalities. In cases where multiple teeth are affected or missing, panoral films are used.

Photographs

Clinical photographs are also a useful aid, particularly for assessing aesthetic impact.

Assessment of Fluorosis

With the widespread introduction of fluoride toothbrushing programmes in Scotland and the introduction of topical fluoride applications within the Childsmile programme3 it is important to be aware of the levels of fluorosis (see Appendix 2 Glossary) in the population.

Mild fluorosis causes the teeth to have a white, spotted or lacy appearance whereas severe fluorosis results in the enamel being markedly hypo-mineralized; such enamel can be brown and prone to breaks and excessive wear. Recent research suggests that teeth with mild fluorosis can be considered aesthetically preferable to non-affected teeth124

Fluorotic lesions are usually bilaterally symmetrical and tend to show a horizontal striated pattern across the tooth. The defects might consist of fine white lines or patches, usually near the incisal edges or cusp tips. They are paper-white or frosted in appearance like a snow- capped mountain and tend to fade into the surrounding enamel.

Diagnostic Aids for Fluorosis

Good clinical photographs will provide a useful clinical record, assist diagnosis and allow pre- and post-operative comparisons for those cases where restorative treatment is carried out.

Assessment of Dental Trauma

Traumatic dental injuries are common, with the most common injuries to permanent teeth occurring secondary to falls, followed by traffic accidents, violence and sports. Indeed, ~15% of 15-year-old boys and 10% of 15-year-old girls show evidence of dental trauma to their anterior teeth. Many sporting activities have an associated risk of orofacial injuries as a result of falls, collisions and contact with hard surfaces, and people who participate in certain sports would benefit from using a properly fitted mouthguard131,132. Trauma also occurs frequently in the primary dentition of 2–3-year-old children when motor coordination is developing

Although patients are largely concerned with the aesthetic consequences of dental trauma, it is the effect of trauma on the health of the dental pulp and periodontal ligament that is most likely to affect the long-term prognosis for the teeth involved. Prompt and appropriate initial management of trauma (e.g. ensuring all exposed dentine is protected as soon as possible with a restoration), together with accurate assessment of pulpal health over the long term, can favourably affect the outcome134-138. This section covers the assessment of patients attending for routine dental care who give a history of dental trauma to the permanent anterior dentition. The management of patients presenting as an emergency with dental trauma is discussed in the SDCEP guidance ‘Emergency Dental Care’.

Diagnostic Aids for Dental Trauma

It can be difficult to reliably assess the health of the dental pulp because all the available tests are inevitably indirect, with the pulp being enclosed within the tooth. The following tests might be useful when the dental pulp of anterior permanent teeth is perfused. However, the results of the tests must be interpreted carefully. Many of the tests are more reliable when applied to several of the anterior teeth, and the results compared.

History of symptoms

A reported sensitivity to cold (e.g. ice cream) indicates a tooth might be vital, whereas a history of swelling and tenderness on biting would suggest dental abscess subsequent to pulpal necrosis.

Colour

Grey coronal discolouration indicates haemoglobin breakdown products secondary to pulpal necrosis, whereas an orange/yellowish tinge might indicate pulp canal obliteration, and so a vital pulp.

Transillumination

Place a dental mirror behind the teeth and, viewing the palatal aspect of the teeth, compare the colour of the crowns as the light from the overhead lamp shines through them. Grey discoloration usually indicates pulpal necrosis.

Tenderness to percussion

Gently percuss each tooth in turn, in an axial direction, with a mirror handle, and assess tenderness.If tender, this might indicate pulpal necrosis but might also be a result of occlusal interference, or increased cellular activity associated with revascularisation. Ankylosed teeth might give off a cracked-plate sound but this does not imply the presence of a necrotic dental pulp.

Mobility

Using something hard, such as the mirror handle, gently move each anterior tooth in a palato–buccal direction, observing closely for any tooth showing non-physiological movement, which might be associated with pulpal necrosis, occlusal interference or just recent trauma.

Ethyl Chloride and Electric Pulp Test

The results of these tests can be unreliable in vital teeth with immature root development and in vital teeth, post-trauma. It is very important to compare the response from several teeth, and usually worthwhile including a non-traumatised lower incisor to assess a positive response. For a more reliable response, place the electric pulp tester probes on the incisal edge.

Radiographs

Radiographs are useful to assess dental trauma. Radiographs of any traumatised teeth and their supporting structures must be taken as close to the time of injury as possible. The type of injury might influence the type of radiograph that can be taken.

Photographs

Clinical photographs of the affected teeth and soft tissues can provide useful information for the clinical record.

Occlusal Assessment

There is a great deal of debate about the importance of occlusion in dentistry but as there are few dental treatments that do not involve the occlusal surfaces of the teeth, assessment of the occlusion is advised.

Centric occlusion (CO) is the most easily recorded occlusion and is the state of maximum intercuspation between upper and lower teeth. It is also called the intercuspal position, bite of convenience or habitual bite as it is the occlusion to which the patient is accustomed. Centric relationship (CR) is not an occlusion but is a jaw relationship; therefore, it does not need the presence of teeth to be determined. It can be defined anatomically, conceptually and geometrically.

Orthodontic Assessment

An orthodontic assessment is routinely conducted after the permanent incisors have erupted and until the permanent dentition is established. The British Orthodontic Society49 recommends that a simple orthodontic examination should be undertaken by the primary care team to detect malocclusions. This includes assessment of the:

Ectopic or Displaced Canines

The upper permanent canine is second only to the mandibular third molar with respect to the frequency of impaction and is slightly more common in females. The canine should be palpable buccally by 8–10 years and if not palpable by 10 years of age requires investigation and treatment.

Balancing/compensation

When carrying out extractions it is sometimes necessary to consider balancing extractions (extraction of the contralateral tooth) or compensating extractions (extraction of the same tooth in the opposing arch).

First Permanent Molars

When extracting any first permanent molar (FPM), the optimum occlusal result will be obtained when the bifurcation of the lower second molar is seen to be forming on the OPG, usually around the age of 8½–10 years

Diagnostic Aids for Orthodontics

Radiographs

Radiographs can be useful in the diagnosis of delayed eruption to identify problems or missing teeth. The decision to expose a radiograph must be based on sound clinical indications and radiography must not be part of routine screening.

Study Models

Study models can provide a permanent record of the dentition at a point in time and so provide a useful tool for monitoring a developing (mal) occlusion.

Photographs

As with other areas, clinical photographs can be useful to assess or monitor a condition

Assessment of Dentures

Patients can wear dentures for many years. Therefore, it is important to assess dentures at each review appointment to identify whether any adjustments or replacements are required

Diagnosis and Risk Assessment

There is now evidence to suggest that the ‘risk’ (probability) of developing oral disease can be affected by modifying factors that include risk and protective factors, behaviours and clinical findings that are associated with the development of oral disease1. However, patients have wide variations between their susceptibility to disease, the likelihood of early disease progressing and the speed of disease progression, if it occurs144. Therefore, it is important to collect patient-specific information to help the practitioner assess each patient’s individual risk of developing both common and less common oral diseases and conditions, and develop a personal care plan that includes appropriate preventive advice and treatment options to reduce the patient’s risk level (see Section 6).

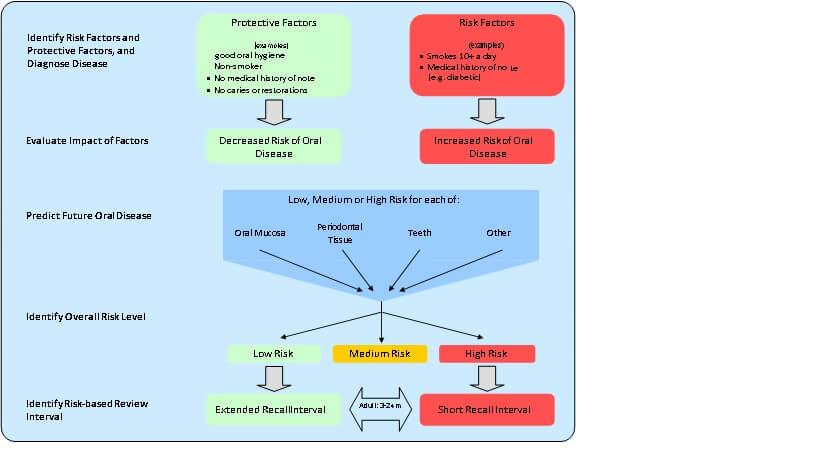

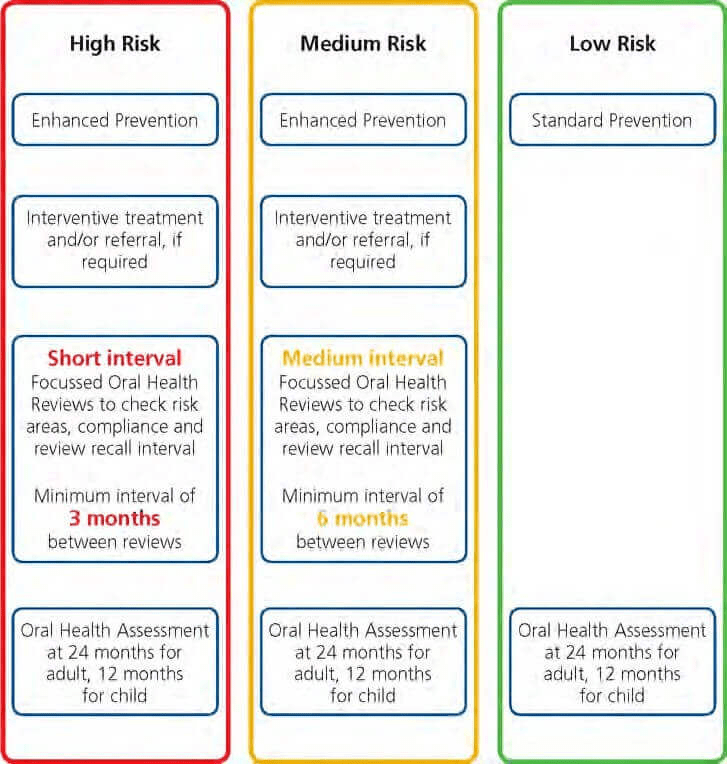

In the past, it has been standard practice to use a recall interval of 6 months for all patients regardless of the oral health needs of the patient. However, following a review of the evidence and a review of clinical opinion regarding what is best practice, the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)1 has recommended that the recall interval is based on the individual’s risk of oral disease. Consequently, patients identified as having an increased risk of developing oral disease might benefit from a short recall interval, whereas patients identified as having a low risk might need to be recalled less frequently (i.e. have a longer recall interval) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Using risk assessment to identify a review interval

The Faculty of General Dental Practice5 and NICE1 identified three key areas where they felt assessment of risk factors is important to determine the dental recall interval:

Risk Assessment Process

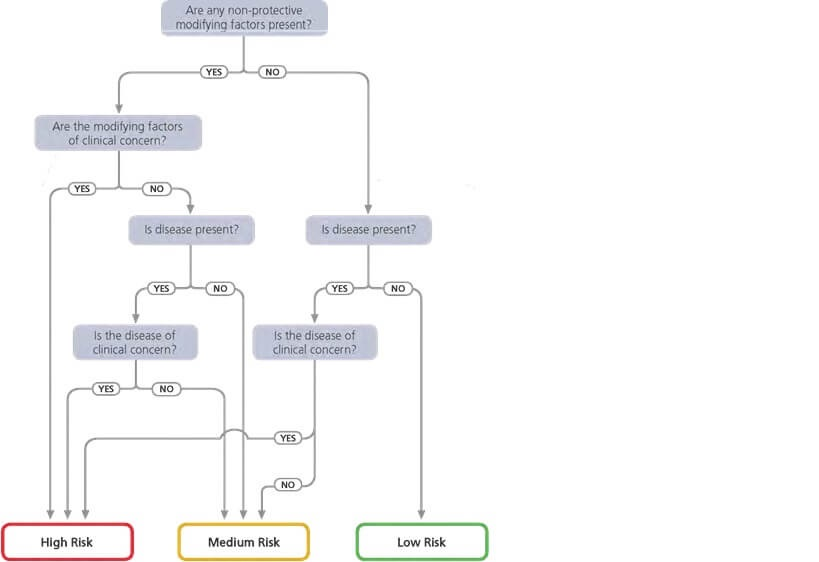

Although the term ‘risk assessment’ might be new to some in this context, clinical risk assessment is not a new concept and has been carried out intuitively by practitioners over many years. It can be thought of as comprising the following stages:

This brings a structured systematic approach to the process. Furthermore, using review intervals that are risk-based facilitates the provision of individualised patient care.

Identifying Modifying Factors, and Diagnosing Disease

The first stage in assessing the patient’s risk of developing oral disease is to identify modifying factors from each element of OHAR that could either protect the patient, or increase their risk.

Modifying factors are identified from information given to the dental team (e.g social history, dental history, medical history) and from information the dentist gains from examining the patient (e.g. presence and severity of caries, dry mouth, presence of plaque).

Note that protective factors are often the opposite of risk factors; for example, a protective factor is good oral hygiene (i.e. twice daily brushing with fluoride toothpaste, daily flossing) and a risk factor is poor oral hygiene (e.g. irregular use of toothpaste, poor brushing technique, no flossing). Some risk factors are oral disease itself (e.g. existing caries is a risk factor for future caries), and therefore the clinician needs to diagnose current disease to identify not only what problems need to be addressed but also to inform the risk of future disease.

Evaluating the Impact of Modifying Factors

After modifying factors have been identified, the dentist needs to use balanced, reasoned clinical judgement to weigh up and evaluate the impact of these factors in relation to each patient’s past and current disease experience.

Although many factors are necessary for disease to develop, they themselves are not always sufficient on their own to cause disease in every patient. Both periodontal disease and dental caries are multifactorial diseases and a combination of factors affect whether they develop and progress in a given patient.

The past and current disease of each patient is the result of the effects of the risk factors and protective factors that the patient has been exposed to in their lifetime, and therefore can give an indication of the influence of the combination of these factors (if known) on the development of oral disease in a given patient. Indeed, past caries experience is the most reliable predictor of future caries experience10.

However, it is also important to be aware of possible inaccurate self-reporting by patients (e.g. alcohol consumption, dietary habits), which might limit the usefulness of some factors in assessing the patient’s risk. Furthermore, the modifying factors for each patient can change over time. It is therefore essential that at each review appointment the modifying factors and their impact are reviewed for each patient.

Predicting Future Disease

Figure 3 shows a simplified illustration of the assignment of a risk level for any element of OHA.

Figure 3 Assigning a risk level for the development of oral disease

Although there is evidence to support an association between certain factors and oral disease1, there is insufficient evidence to ‘weight’ the different factors. Indeed, there have been several attempts to summarise the risk assessment as a single number but there is limited evidence to support this type of approach. Some software packages attempt automatic risk classification but it must be appreciated that the validity of these estimates is not yet known.

Therefore, when assigning a risk level, the clinician’s knowledge of the patient (including their attitude to care and ability to cooperate) and knowledge of the patient’s past rate of disease progression, together with the clinician’s assessment of the impact of risk factors and protective factors in each individual patient is the best available approach

Identifying the Overall Risk Level

The risk level for each of element of the OHA can differ and so it is recommended that the dentist assigns an overall level of risk for each patient taking account of the risk levels identified for each key element of the OHA. In many cases, the overall risk level may be judged to be the same as that of the OHA element with the highest risk level.

The overall risk level will then help inform the review interval.

Identifying a Risk-based Review Interval

Based on the identified overall risk level for each patient, and the clinician’s knowledge of the patient, a review interval that is specific to the needs of the patient can be assigned as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)1.

NICE recommends the following shortest and longest intervals between one assessment and the next assessment:

To operationalise this approach, it is recommended that after the first Oral Health Assessment, if it is considered necessary, the patient receives Focussed Oral Health Reviews (FOHRs) at variable risk-based intervals. At a FOHR, primarily those elements previously rated as high or medium risk are reassessed (see Section 6 for further details). Subsequently, it is recommended that patients receive a full Oral Health Assessment every 24 months after their last full OHA for adults and 12 months after their last full OHA for children. This ensures that each patient has a regular comprehensive assessment and reflects the maximum intervals recommended by NICE.

As shown in Figure 2, a patient who has an imbalance of modifying factors in favour of risk factors will have an increased risk of oral disease and therefore is likely to benefit from a short review interval. This will enable effective monitoring to help prevent the initiation and/or further development of oral disease. By contrast, a patient who has an imbalance of modifying factors in favour of protective factors will have a decreased risk of oral disease and thus a more extended review interval is suitable.

It is suggested that at the first OHA an initial review interval period is identified based on the individual needs of the patient. For new patients, the practitioner is unlikely to be able to predict accurately how oral disease might progress as they will have little knowledge of the patient. It is therefore advisable initially to assign a review interval that is conservative (i.e. shorter review interval). At the next and following review appointments, if no new problems are encountered the review interval may be extended incrementally up to the maximum interval recommended by NICE1

A checklist is provided to assist with recording which elements of assessment have been conducted as a particular visit and the outcomes of the assessment, including risk levels assigned for individual elements, the overall risk level and the review interval. A form which can be used to help communicate this information to the patient is also provided (Patient Review and Personal Care Plan).

Personal Care Plan and Ongoing Review

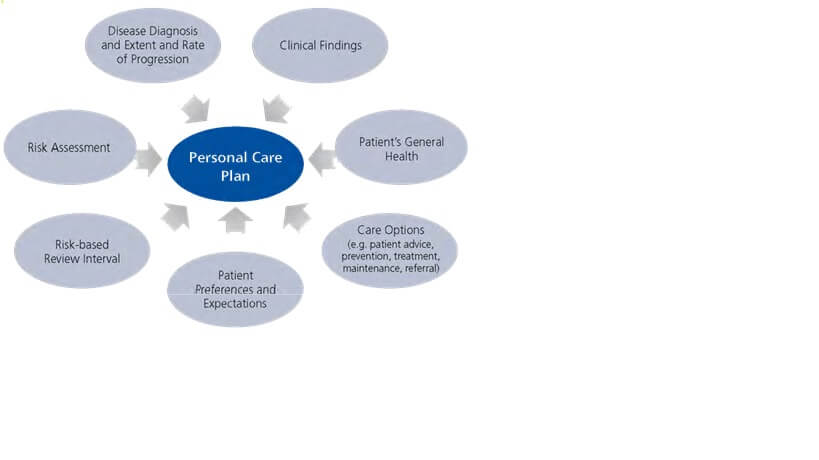

The personal care plan is a risk-based long-term plan that is designed to address the patient’s individual oral health improvement and maintenance needs.

For a personal care plan to meet the changing needs of a patient, it is important that on registering with a dental practice, each patient receives a baseline comprehensive Oral Health Assessment (OHA). For adults, this is repeated after 24 months. For children, the first comprehensive assessment should be conducted as early as possible, and no later than three years of age, and repeated at 12 month intervals. In addition, during these time periods Focussed Oral Health Reviews (FOHRs) can be carried out (see Section 6.2 for details). Both the number of FOHRs and the intervals between them will vary depending on the patient’s risk of future oral disease.

After the dentist has made their assessment of the individual patient’s risk and has diagnosed current disease, to develop a personal care plan the dentist needs to

for low risk patients who are not new to the practice, the next assessment will be an OHA (after 12 months for children or 24 months for adults). For patients assessed as at medium or high risk, the next assessment will be a FOHR carried out at an agreed risk-based interval.

As described in Section 5, for low risk patients who are not new to the practice, the next assessment will be an OHA (after 12 months for children or 24 months for adults). For patients assessed as at medium or high risk, the next assessment will be a FOHR carried out at an agreed risk-based interval.

A personal care plan can include:

A personal care plan need not include all of the above but will always include patient advice (even it is advice for the patient to carry on with their current oral hygiene routine) and an individualised review interval. In some cases, the personal care plan might be more elaborate and complex, but it is increasingly advised that more extensive care plans are best carried out after stabilisation of disease is achieved and after the dental team has had the opportunity to assess a patient’s response to preventive advice and care.

Developing a Personal Care Plan

As illustrated in Figure 4, several factors need to be considered when developing a personal care plan. The treatment and management of patients can be influenced by any modifying factors including risk and protective factors and clinical findings observed during assessment (whether from an assessment of the head and neck, the supporting structures or the teeth themselves). These clinical findings, relating most commonly to dental caries, periodontal health and the oral mucosa, which might or might not be directly associated with the development of oral disease, will impact upon the choice of the most suitable treatment options for the management of a particular patient at a given time. It is therefore important to take note of all relevant findings when planning care for a patient as this will aid the planning process itself, aid communication with the patient and is useful from a medico-legal standpoint to be able to show how care plans were arrived at (see Figure 4).

Other clinical conditions (e.g. white lesions in the oral mucosa, mucosal ulceration) might represent risk factors for the development of more serious oral mucosal disease. Some lesions might require referral to a specialist, which will be included in the personal care plan, whereas others might simply require periodic review in primary care.

The personal care plan also needs to take note of the patient’s preferences and their willingness and ability to comply with any proposed plan. Therefore, it is important that the personal care plan is discussed with each patient and the patient is provided with a written personal care plan that details all proposed elements. In some cases, particularly with child patients, it might be necessary to complete any required treatment in stages, only moving on to more invasive procedures when the patient is able to cope (see the SDCEP guidance ‘The Prevention and Management of Dental Caries in Children’9).

Figure 4 Points to consider in the development of a personal care plan

The components of a personal care plan, including the frequency of assessments, will vary between patients and depend on whether the patient’s overall risk level has been assigned as high, medium or low. This is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Variation in personal care plans for the three risk levels

Not all elements of the personal care plan necessarily need be delivered by the dentist; some can be delivered by other members of the dental team. Details of the roles and responsibilities of the various members of the dental team are outlined in Appendix 3. It is important to highlight to the patient which elements of care will be provided by different members of the dental team. It is also important to detail whether there are any elements that will not be provided or if the dentist and patient have differing views.

Clinical Governance, CPD and Training

It is a requirement of clinical governance and fundamental good clinical practice that all health professionals work to monitor and constantly strive to improve the quality of care they provide. One important aspect of assessing patients is the requirement of dental professionals to produce and maintain adequate patient records.

It is recommended that:

Recommendations for Audit

Topics for audit and review should be chosen carefully to provide information that will improve the quality of each OHA and ensure patient safety. Examples include:

Recommendations for Research

Topics for research investigation in the field of OHAR are those areas that are clinically important and for which there are current gaps in the evidence base. Examples include:

Very satisfying! It was my first time to get assignment help on MBA essay writing. I am really happy with the service. Actually, I needed an urgent assignment help and these experts had done the job fabulously. Thanks for your support!

Best CRM writing service ever! I was unsure about the professional assignment writing services but required a help very badly. It was my friend who suggested me to visit Help My Assignment and submit the details. It was very helpful in finishing my project on time and I got good grades as well.

Me and my friend were in total confusion about how to manage time to participate in a musical event and do assignments on time. We were searching for academic services and found Helpmyassignment. We loved the service and will order projects again.

Thanks for providing instant support! Last weekend, I forget to prepare my assignment when busying in doing other works. My friend had suggested me this site for urgent writing services and I asked for the same. I didn’t expect such fast and quality service.

My teacher assigned me projects on case study. I am not familiar with the topic and need professional help to understand the same. At helpmyassignment, there is a possibility of online chat with experts. It was a great support. I am very happy now.

I was almost near the deadline to submit history dissertation assignment but didn’t able to start the project in the last two days. I called my friend and asked for a quick solution. She told me to hire professionals at help my assignment. I submit the project and mention the deadline. I am very satisfied with the on-time service.

I want to share my experienced with helpmyassignment.com as they gave me guarantee to meet all the requirements of academic writing. The top most quality of the academic writers was that they deliver all my 6 assignments before the deadline without any delay and with Plagiarism reports. They never gave me a chance of any complaint regarding quality as they deliver writing services on time and I have scored very good marks in all 6 assignments.

DOHA: User ID- 14567

I am so much glad with the customer support service of helpmyassignment.com. The customer care agents were very quick to respond over the e-mail and telephonic conversation/WhatsApp. They have multichannel support. Thank you to all the people who helped me a lot to deliver the academic projects and put great efforts to complete it in stipulated time frame.

Thalia K Australia User ID: 14787

I am a student of MBA in a reputed University in Australia and in my last semester there was a need to complete some of very difficult assignments. The college assigned me the hardest tasks that was financial case study and I was little bit depressed. After that, I heard about helpmyassignment.com and contacted them. They provided me a high quality student level assignments due to which I passed with very good marks. I appreciate your experts for helping me out.

Mercy K, Singapore: User ID-14545

I am extreme happy to receive writing services of helpmyassignment.com as there was no issue of plagiarism, content, formatting and it was well referenced as well. The team was very supportive to provide me PhD level assignment with original content and depth research. I really recommend HelpMyAssignment to all the students of Management Colleges.

James P, USA: User ID- 14985

I contacted helpmyassignment.com, and they said," First check the draft free of cost and then pay as per your satisfaction" I accepted and shared my engineering order, they have sent draft next day and I was very confident after checking the draft that I am in right hands. The full assignment was very well drafted and quality was very good. I scored very good Marks.

Ahmed, UK: User ID- 14900

I am so Glad that I have come across this HelpmyAssignment.com as they provide you with exceptional services. They ensure that you take your work very seriously and provide your assignment before the due date so that you can check it carefully before final submission. I have done many assignments from them and always scored more than 80% in each order. I am happy to be choosing these guys for help as they always allow you to ask for rework free of cost if not happy which is rare.

Maria- Order ID- 6787, Australia

I was skeptical about hiring the online assignment for my Nursing Assignment. Thanks to HelpMyAssignment.com! The experts appointed for my order have done a great work and I have scored 95%. I must say the company is undeniably genuine, secured, and effective from all aspects. It was a well-defined policy. What more can I ask for.? Perfect.! Thanks once again, I recommend all my friends for your services.

Mohamed- Order ID- 6677, UK

Thank you so much for your outstanding and A Grade work following all instructions perfectly. 100% better than other service providers. You provide high quality work within the time frame, exactly to the point. I am proud to be associated with you. You are an excellent company with highly experienced staff and high quality of work.

Antonio- Order ID- 6210, USA

We deliver the best price guarantee to all the students and make sure that the assignment help services for all subjects do not cost much. In addition, we are also ready to deliver some outstanding and exclusive offers.

Each and every assignment that we offer are original, fresh and 100% plagiarism free. Thus, students do not need to feel worried about the fact of whether the content is copied or not.

We ensure that all the data given or shared with us will remain safe with us because we never disclose them to any of the third party. You don't worry about the fact what will happen to the data.

We have the best team of PhD writers and they have got the degrees from leading universities from different parts of the world. You will get to have constant assistance from such industry experts who will help you to complete the research work in the best possible manner.

We make sure to conduct out and out in-depth analysis for the paper we work on. All the information and details given in the paper are true to the best of our knowledge. All the data that we use in the papers are backed with authentic sources and include valid details. This would help you to feel your mind with great confidence while submitting the task to the teacher.

Open an assignment from on our website and fill it up correctly Feel Free to chat with our representative and inquire about your query for free of cost.

Get your Assignment completed at the best prices ! Pay for your assignment through Credit Cards or Paypal at any time you want.

Our hIghly skilled professional writers ensure you get online assignment help within the deadlines. Makes several revisions for free till 15 days of the delivery.